What does Neuroscience have to say about Free Will?

Are we really in control of ourselves?

The debate about Free Will has its roots from Plato and Aristoteles in the IV century BC, to modern times. Many have tried to answer this question, from philosophy to theology and science: Are we in control of our decisions?

In this article, I will review the current state of this question, from the lens of philosophy, theology, and neuroscience.

How did we get here and where do we go from here?

Of course, philosophy, such as theology and neuroscience, are broad fields of science with many authors that discuss and see things differently.

That’s why, we’ll describe from a general perspective the points of view on Free Will from these scientific fields.

Philosophy standpoint

For philosophy, Free Will is “the supposed power or capacity by an individual to make decisions or perform actions independently, from various alternatives, of any prior or state of the universe”.

We will see in greater detail later on that these decisions can’t be performed independently from prior states of the universe.

However, the individualistic approach presupposes the term “free-will-determinism”, in which individuals are totally responsible for their own behavior, without any external factors having enough impact to interfere with the control of their decisions.

To go further, I will use the theory of Free Will from two major philosophers with different sayings on the subject: Plato and Hegel.

Plato

For Plato, human beings are free to form belief systems, which create conditions or causes necessary for asserting the Will. In other words, one is free to change their decisions and beliefs which lead to different outcomes, that determine an individual's path in life.

The notion of “path” is linked with the notion of “destiny”, presupposing that there is already a route map describing the end of one's life. Very arguable.

Nonetheless, Plato also introduces the importance of moral choices for the soul to achieve a heavenly state in the afterlife, a “freely chosen morality”, that allows the individual to increase in a way their own free will, and then achieve total integrity.

Hegel

The German philosopher, already influenced by the advances in evolutionary biology, as initial as they were, proposed an evolutionary perspective for the concept of Free Will. He advocated that the universe is part of an evolutionary process, and as it progresses, it unfolds up to its full expression.

This progression is similarly attributed to the human experience. He argued that:

“The Will is Free only when it does not will anything alien, extrinsic, foreign to itself, but wills itself alone — wills the Will”.

To be short, Free Will only is achieved when one eliminates all of the preconditions of oneself (i.e., culture, social relationships, learned behavior, ethnicity). Again, very arguable.

So, for philosophy, we can argue that Free Will is the sovereign choice to be free, and for that to happen, it must be the case that this decision is totally abstracted from external factors. You make the choice, and nothing ultimately causes you to make the choice other than the fact that you choose it, not any cultural, or biological determinism, but you.

Well, let’s step a bit further.

Theology enters the debate

To introduce Theology, I found a quote that clears out immediately the theology standpoint:

“Most scholars argue against free will, however, once theology enters the debate in favor of free will; the spiritual concepts of the Godhead and soul alter the dynamics of the argument”

The concept of God for theology allows the individual to pose faith as an argument, therefore the reasoning principle of philosophy loses the power of logic.

Let’s use as an example the theological side that argues that there’s indeed a Free Will.

Theology makes a clear but relevant case on sin. You are free to choose one thing or the other, but before faith, all actions have the corruption of sin. So unbelievers, like myself, can do “external” good work in our community, with society, and nature, but it’s not enough because we don’t have faith in God.

God is almighty and knows the past, present, and future. If that is true, then why are actions necessary? Why do we need to behave and believe in a way that makes God satisfied if he/she/it knows everything?

Well, Theology has an answer. God, in his eternal present, is the first cause of all things. God belongs to a different order than human beings. How convenient!

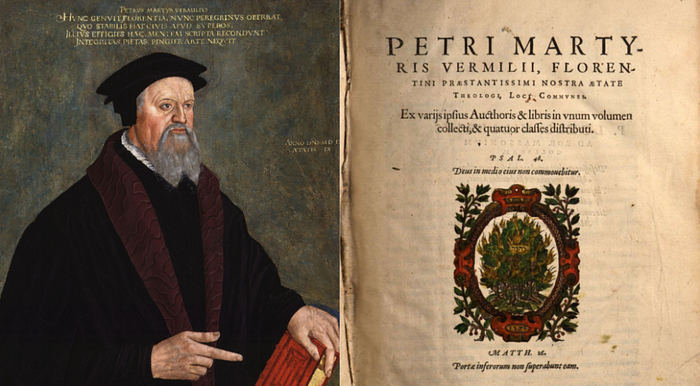

The theologist Peter Vermigli went a step further and asserted that God causes everything, but humans still retain freedom in the realm of what he calls secondary cause.

We humans, for Vermigli, are in the order of causality — cause and effect — of the second order, known as creaturely causality. God is divine, so it’s the first cause.

So then, you would be asking:

How do we have free will if God exists and then he/she/it is eternally present — past, present, and future?

Well, in this sense, Vermigli argues that you have free will (creaturely causality) because you live in the secondary cause, while God has divine causality and lives in the first cause, but this first cause doesn’t necessarily have to affect your freedom of choice.

That’s that. Theology, as was said previously, heavily bases its theory on faith, and that should be respected.

The elephant in the room: Neuroscience and the advances in Biology and technology

I see a big difference between theology and natural sciences in one aspect: one has autocorrection, while the other runs deeply on beliefs.

This autocorrection can be best explained with one of the most renowned experiments achieved in the field of neuroscience.

In 1983, Benjamin Libet tested free will asking himself whether the conscious intention to act is preceded by unconscious brain processes.

This comes as a counter-argument to the abstract notions of philosophy and theology when more concrete questions are presented, such as:

Can our conscious decisions be predicted from measured preceding neural activity or not and whether we have any control over what we decide?

The experiment setup was simple. Two elements were put to test simultaneously: electrophysiological measurement of brain activity preceding intentional attention and subjective timing of conscious intentions.

Participants had to carry out a simple action such as flexing their wrist or pressing a key.

While forming the intention to act, the participants had to observe a revolving spot on a clock face, and, the moment after they executed the action, they had to indicate on a clock face when exactly they became aware of the intention to act. In this experiment, Libet calls this intention to act as W.

As the graph shows, the W is preceded by the actual motor response (Action) by about 200 ms. This indicated that participants can distinguish the intention to act from the act itself.

This is not it, however. The RP, or readiness potential, is a specific brain wave that, as seen in the graph, precedes W by 350 ms.

With this in mind, Libet argued that the fact that a brain wave precedes the conscious intention by a few hundred milliseconds shows that the conscious intention cannot be the cause of action, but rather is the consequence of brain processes preceding it.

In other words, by Libet experience, there’s no free will, everything is predetermined by neurological connections.

However, Libet’s experiment had some drawbacks. The main criticisms came from the ecological validity of the study — which was in a controlled setting and not in a natural one — and whether the method of reporting the conscious intention might alter the process under investigation.

Critics argued that Libet’s experiment does not refute Free Will, but on the other hand, his work must be reinterpreted as a decision-making example. In their view consciousness and control over decisions are still highly relevant, although some decisions are taken unconsciously.

With all of this in mind, one could argue that the question about free will is not yet solved, and further experiments should be developed to answer it. Science is a gradual, constructive, and autocorrective mechanism.

Well, all of that didn’t care Robert Sapolsky, who boldly argues:

The world is not deterministic and there is no free will. Show me one neuron that has some cellular semblance of free will.

Let’s see further.

Robert Morris Sapolsky is a neuroscientist and primatologist at Standford University and a professor of biology, neurology, and neurosurgery.

He argues that we above all are biological organisms, nothing more and nothing less, and that nothing we do is separated from our biology. The biology of our behavior reflects the interactions of all levels of analysis — neurochemistry, endocrinology, evolution, and genetics — as well as their interactions with the social world.

Everything that happens is caused by something prior, every behavior is due to something that obeys the rules of biology and the laws of the physical universe.

Robert M. Sapolsky

This perspective is rather different than the ones proposed by philosophy and theology. It restricts oneself to think of only as an individual, an atom that just exists and achieves Free Will by their own sovereignty of choice or by God’s hand.

No, this concept allows us to, I believe, think of our decisions as a consequence of our morning routine, cultural background, epigenetics, the environment we are in, the food we eat, and so on. This Sapolsky calls “Distributed Causality”.

As an example, let’s see the case of Phineas Gage.

Phineas Gage was a 25-year-old worker at the construction of railroads. He was in charge of detonating the rocks that formed the mountain, but in a moment of carelessness, an iron bar jumped from a badly planned detonation. The iron bar went through the left cheek of Phineas' face and came out through the right side of the skull, without any bleeding whatsoever.

Two months later, he was working again. However, Phineas had changed.

The iron bar took a big part of Phineas prefrontal cortex, and his behavior changed. Before the accident, Phineas was portrayed as a kind, conciliatory, and responsible man, but now was seen as suspicious, irritable, and constantly quarreled with his colleagues.

He jumped from job to job because of misbehavior with his peers.

He ended up being exhibited in the circus and died by the age of 38.

For Sapolsky, this example is remarkably clear of how a change in one’s brain structure changes everything about decision-making and control, which he argues, is a strong case to rule out Free Will.

We’ve seen the perspective on Free Wil from the philosophical, theological, and neuroscience perspective, each with its arguments and counterarguments.

From my personal view, I agree with Sapolsky standpoint on how distributed causality can offer us a clearer answer to the question of Free Will, by reducing the individual to a mere absorber of external and internal factors and how these play out to inform and cause our decision making.

This is, and will be, an eternal debate however. I think that the existence of an omnipotent being shouldn’t be the excuse to not hold someone accountable for ones actions, but faith should never be disrespected.

In the end, whether we have or not have Free Will, it’s up to you how you behave within society and try to become the better version of yourself.